SECURE Act Planning Opportunities

Just before the new year, the SECURE Act, a bill intended to improve the retirement outlook for millions of Americans was signed into law. We highlighted the main provisions of the new law in an earlier blog post. A new law that changes some of the rules governing how you save for retirement is bound to create advantages for some and disadvantages for others. Our objective isn’t to point out who the winner and losers are out of this, but to offer planning strategies to consider in light of the new rules.

First, we will cover a few foundational concepts that are relevant for the planning strategies that follow.

Overview of US Tax Brackets

The first one is simply tax brackets. The chart that follows is the U.S. Federal tax brackets for 2020. This may already be familiar to you. As you likely know, at a low income, you pay a low tax rate, and a larger tax rate at higher income. Of course, there are different filing statuses depending on if you are single or married, among other factors.

The important thing to consider here is that two households will potentially be taxed at very different rates for the same income. For example, an individual making $250,000 will be in the 35% tax bracket, while a married couple, filing jointly making the same income will be in the 24% tax bracket.

Step Up in Basis Upon Death

Appreciated assets held outside of a retirement account (or other tax protected structure such as an annuity) receive a “step up in basis” upon the death of the owner. Think about it this way. The house that you bought in 1978 for $75,000 is now worth $1,500,000. If you sold it, you would have a taxable gain of $1,425,000 (setting aside the primary residence exclusion and improvements over the years). If it was sold after your death, the basis would step up to the value on your date of death. Your heirs could then sell the property with no (or virtually no) taxable gain. It’s the same with the shares of IBM that your uncle bought for you when you were five.

However, assets in certain types of accounts do not receive a step up in basis, most notably traditional IRAs and employer retirement accounts such as 401(k) plans. Roth IRAs do not receive a step up, but they don’t need one because distributions are tax free. Annuities also do not receive a step up. This makes IRAs and annuities the most tax expensive type of accounts to inherit.

Income Tax Gap Years

For many, your highest earning years are in the latter years of your career. This is often when you will be in the highest tax bracket you have ever been, or will ever be. The graph below gives a hypothetical example of a married couple who were high earners in their late 50s and into their 60s before retiring at age 63. As you can see, their income put them in a high tax bracket. After retirement, they still had some investment income, but without their high earnings, they found themselves in a very low tax bracket. This is the case until age 70, when they began Social Security payments, then age 72 when their income spiked due to required minimum distributions from their IRAs.

The period from age 63 to age 69 for this hypothetical couple presents an opportunity to realize additional taxable income at very low tax rates.

The Widow Tax Penalty

As if losing a spouse isn’t hard enough, most widows will find themselves in a higher tax bracket after the death of their spouse. This is because of the change in their tax filing status. Unfortunately, if you are widowed, in most cases, you go from filing Married, Filing Jointly, to Single. As we saw earlier, this means that for the same amount of income, a widow pays a higher income tax than before the death of their spouse.

Again, looking at the same chart as before, assuming the death of a spouse at age 73, you can see that the top income tax bracket goes up from 24% to 32%.

SECURE Act Planning Strategies

Partially Bypass Spouse as IRA Beneficiary

Traditionally, most married couples name one another as their sole primary beneficiary, and their kids as the contingent beneficiaries. After one spouse dies, the surviving spouse then names the children as the primary beneficiaries. Upon the second spouse’s death, the kids inherit the entire combined IRA.

Considering the fact that SECURE Act eliminated the “stretch” IRA for most adult child beneficiaries, you should consider naming kids or other heirs as partial primary beneficiaries in addition to your spouse. Assuming you and your spouse do not die in the same year, this allows beneficiaries to effectively stretch distributions over a greater number of years. If death occurs ten years or more apart, the beneficiaries effectively get two ten year inherited IRA RMD windows, rather than one. This wider distribution window increases the possibility of a lower income year in which to take larger distributions.

The biggest caveat to this strategy is to determine whether or not the surviving spouse will need all of the IRA funds. If they will need all of it, then this is not an effective strategy. However, if there is more than enough resources to provide for the surviving spouse, this strategy is worth considering.

Example:

Fred and Wilma, both 75, are a married couple with two adult kids, Pebbles and Elroy. Fred and Wilma each have an IRA with a $500,000 balance. Fred dies in 2020, and Wilma dies ten years later at age 85 in 2030. Taking asset growth and distributions out of the picture, with the traditional beneficiary designation method, Wilma would inherit Fred’s entire IRA and roll it into her own (using the spousal rollover), leaving her with a $1 million IRA. After Wilma’s death, Pebbles and Elroy would each inherit a $500,000 IRA, which is subject to the 10 year RMD rule.

Using the “partially bypass spouse” strategy, Fred and Wilma name each other 50% beneficiary, and Pebbles and Elroy 25% each. After Fred dies, Wilma receives $250,000, while Pebbles and Elroy each receive $125,000, which they have ten years to withdraw. When Wilma dies, they inherit the remaining $750,000, or $375,000 each, which they then have another ten years to take full distribution. By splitting up the IRA inheritances, this reduces the likelihood that the forced inherited IRA distributions will bump Pebbles or Elroy into a higher tax bracket.

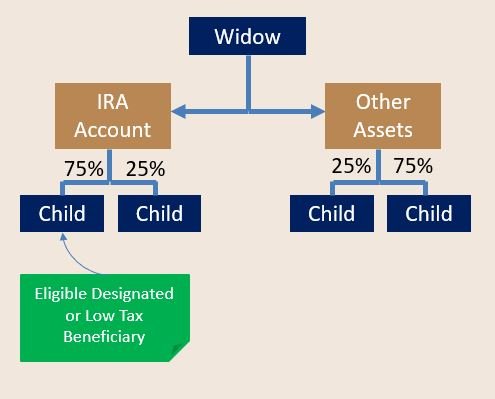

Name “Eligible” or Low-Tax Bracket Beneficiaries

Unmarried IRA owners with children typically name each child equal beneficiaries. After the IRA owner dies, beneficiaries inherit the IRA in equal shares and designated beneficiaries have 10 years to take full distribution. If any of the beneficiaries qualify as an eligible designated beneficiary, that person is allowed to stretch distributions based on life expectancy.

With this in mind, the after-tax value of the IRA is likely greater for the eligible designated beneficiary than it is for the designated beneficiary. That is, unless the eligible designated beneficiary is in a higher income tax bracket.

This brings us to the second point. If you have beneficiaries who happen to be in very different income tax brackets, it’s useful to consider that the after-tax value of the IRA is less for the high income tax beneficiary than it is for the low income tax beneficiary.

The strategy calls for recognizing the difference in the after-tax value of the IRA to your beneficiaries based on their differing situations, whether that is income level or eligibility to stretch distributions. Instead of naming each beneficiary equally, consider allocating a larger percentage to the lower income or the eligible designated beneficiary. If it is important to equalize inheritance amounts to beneficiaries, consider doing so with other assets, particularly assets that will receive a step up in basis, such as non-retirement investments or real estate.

Roth Conversions

If you have a traditional IRA, you should review your expected taxable income near the end of every year. Remember the “Income Tax Gap Years” that I described earlier? What was described was a case of extreme income changes due to retirement. However, your situation might involve changes in income due to variable bonuses or commissions, selling real estate, reducing work for further education or to care for family, among many other reasons. You should consider converting part of your IRA to a Roth in any year in which your taxable income is substantially lower than expected future years.

For married couples, Roth conversions will help to reduce the widow penalty after one spouse passes away. By reducing the size of the traditional IRA, you are reducing the future required minimum distributions.

Beneficiaries of IRAs are often in their peak earning years at the time that they inherit the accounts. For example, an 80 year old IRA owner whose kids are in their 50s are likely in the highest tax brackets they will ever be. If they are more than 10 years away from retirement, the forced distributions from the traditional IRA will be taxed at their highest tax bracket. The inherited Roth has the same 10 year distribution rule, but the Roth distributions are tax-free, even for the inheritors.

Charitably Minded Strategies

If you have a desire to make a substantial charitable gift, either during your lifetime or upon your death, there are some strategies that can maximize the tax benefit of those gifts.

The easiest one is making a Qualified Charitable Distribution (QCD) from your IRA if you are over age 70 ½. According to the Tax Policy Center, an estimated 90% of American taxpayers take the standard deduction since the implementation of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. If you are one of them, your charitable donations are no longer being deducted from your taxable income. By making the donation directly from your IRA (QCD) the distribution of funds from your IRA to the charity is not considered taxable income to you (as all other distributions from your IRA would be, including tax withholding).

At the other end of complexity is creating a Charitable Remainder Trust (CRT) and naming it your IRA beneficiary. The CRT could provide income to someone of your choosing for their life, effectively creating a stretch distribution, and upon their death, the balance goes to charity.

Alternatively, if you would like to make a bequest to your favorite charity upon your death, do it from your IRA rather than naming them in your trust. Most commonly, charitable bequests are dome by designating a dollar amount to go to a charity at death. Because your IRA is not governed by your trust, the bequest has to be fulfilled using other assets such as non-retirement investments which will be receiving a step up in basis. Instead, by designating a charity to receive part of your IRA, they can take their share without paying taxes (benefits of being a charity!)

If You Are Inheriting an IRA...

If you are inheriting an IRA and do not qualify as an eligible designated beneficiary, you have ten years to complete distribution of your inherited IRA. Remember that this does not mean one tenth per year. Instead there is zero required distribution in years 1-9, but 100% must be distributed by the end of year 10.

As an inheritor of an IRA, you should assess your situation and determine if you expect any changes that will cause you to be in a higher or lower tax bracket in the future. If you expect a change that will ease your tax situation (put you in a lower tax bracket in the future), you should delay distribution until that change occurs. Examples of events that may ease your tax situation:

- Upcoming retirement (income tax gap years) or other cut back or stoppage of work such as returning to school or caring for a child or aging parent.

- If you plan to move to a lower income tax state. Even if your income is not expected to change, a move from California to Nevada, for example, will reduce the total taxation of your IRA distributions.

- Plans to get married mean changing your tax filing status from single to married filing jointly.

If you expect a change that will increase your tax rate, you should accelerate distributions before that change occurs. Examples of events that may increase your tax rate:

- An increase in income is expected, such as if you are completing education, apprenticeship, or a residency.

- If you plan to move to a higher income tax state. So, in this case, going from Florida to New York will increase the taxation on your IRA distributions.

The stated intent of the SECURE Act was to improve the retirement outlook for “every community.” Some of the changes brought by the law will likely enable some who did not have access to a company retirement plan to save more for their retirement. That’s excellent news for those impacted in that manner.

For many others, the loss of the stretch distributions caused by the SECURE Act is going to cause a substantial, accelerated tax burden. However, careful planning using the strategies detailed above can help to mitigate some of that tax burden. The appropriate strategy is highly dependent on your situation and the situation of both your beneficiaries and anyone from whom you expect to inherit retirement assets.